On October 21, 2025, TensorWave (the all-AMD neocloud) held an event titled “Massive Scale Training & Inference Panel + Networking” at the very spacious HockeyStack office in San Francisco. Featuring a lot of drinks, pizza, a panel, and plenty of opportunity for mixing, I had a fun time. Let’s get into it.

The Setup

The panel will explore Massive Scale Training and Inference for the enterprise with ScalarLM.

Panelists: A curated lineup of leaders and community builders from leading tech companies and foundations including:

Greg Diamos - Architect, ScalarLM

Molham Aref - Founder & CEO, RelationalAI

Farbod Tavakkoli - Data Scientist, AT&T

Jeff Tatarchuk – Moderator, Co-Founder, TensorWave

I came to this event expecting a deep discussion of the internals of ScalarLM, a unified training / inference stack that runs on AMD GPUs. I wanted to know its low-level internals, performance and profiling details, and the challenges in porting vLLM to run various models on AMD GPUs cleanly and efficiently. I was expecting a discussion of what has been done so far, what doesn’t work, and how things will change in the coming months.

But, none of this happened: the panel was disappointing. Perhaps I should have gone to the PyTorch or Triton Developers Conference instead.1

Turns out that it is “Open Source AI Week” in SF

The Panel

After getting some drinks, we all sat down for the panel at 7pm which lasted around 45 minutes.

The panelists. Ilya substituted for Jeff.

ScalarLM

We began with some pleasantries and then Greg jumped into some slides about ScalarLM.

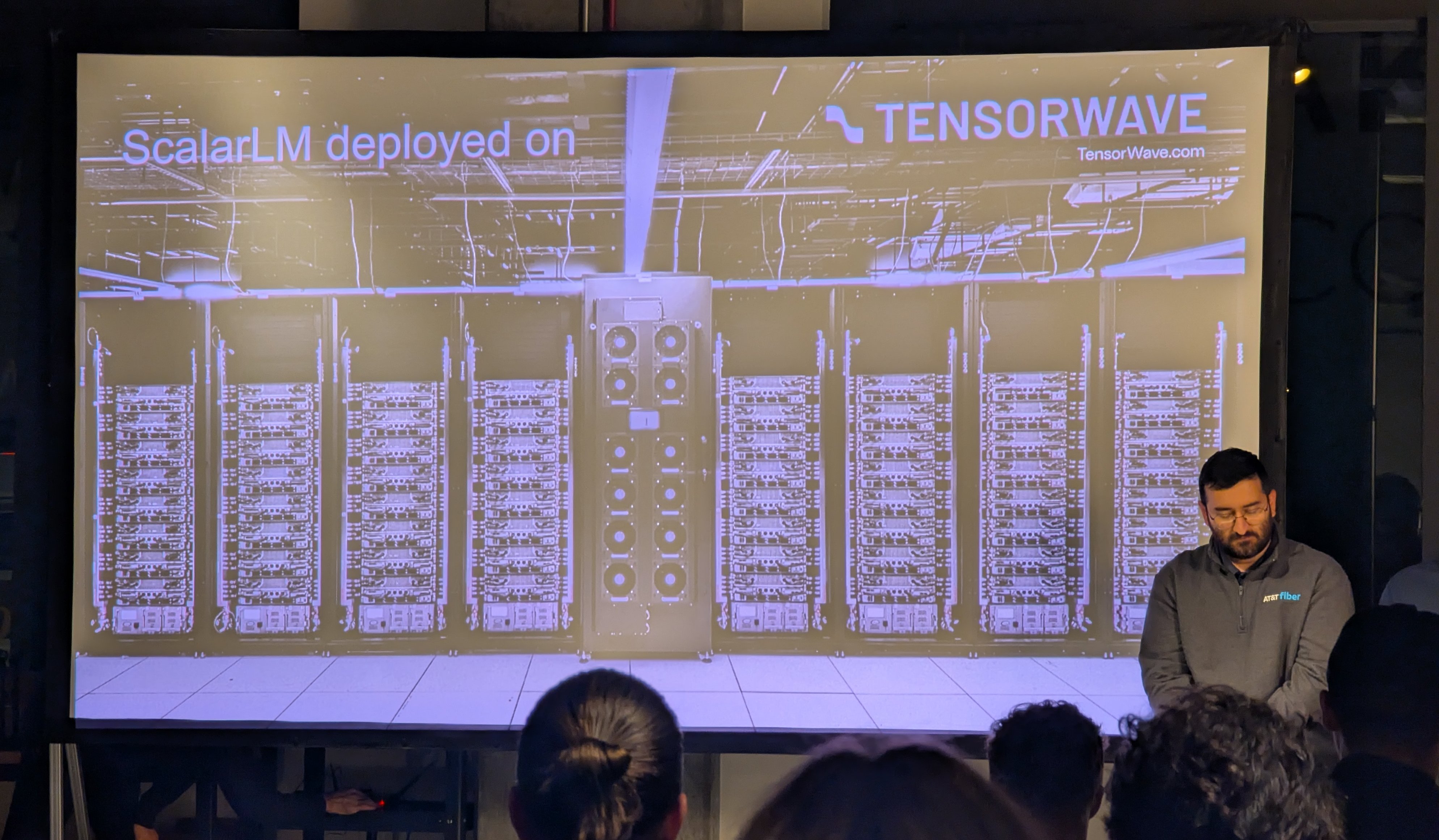

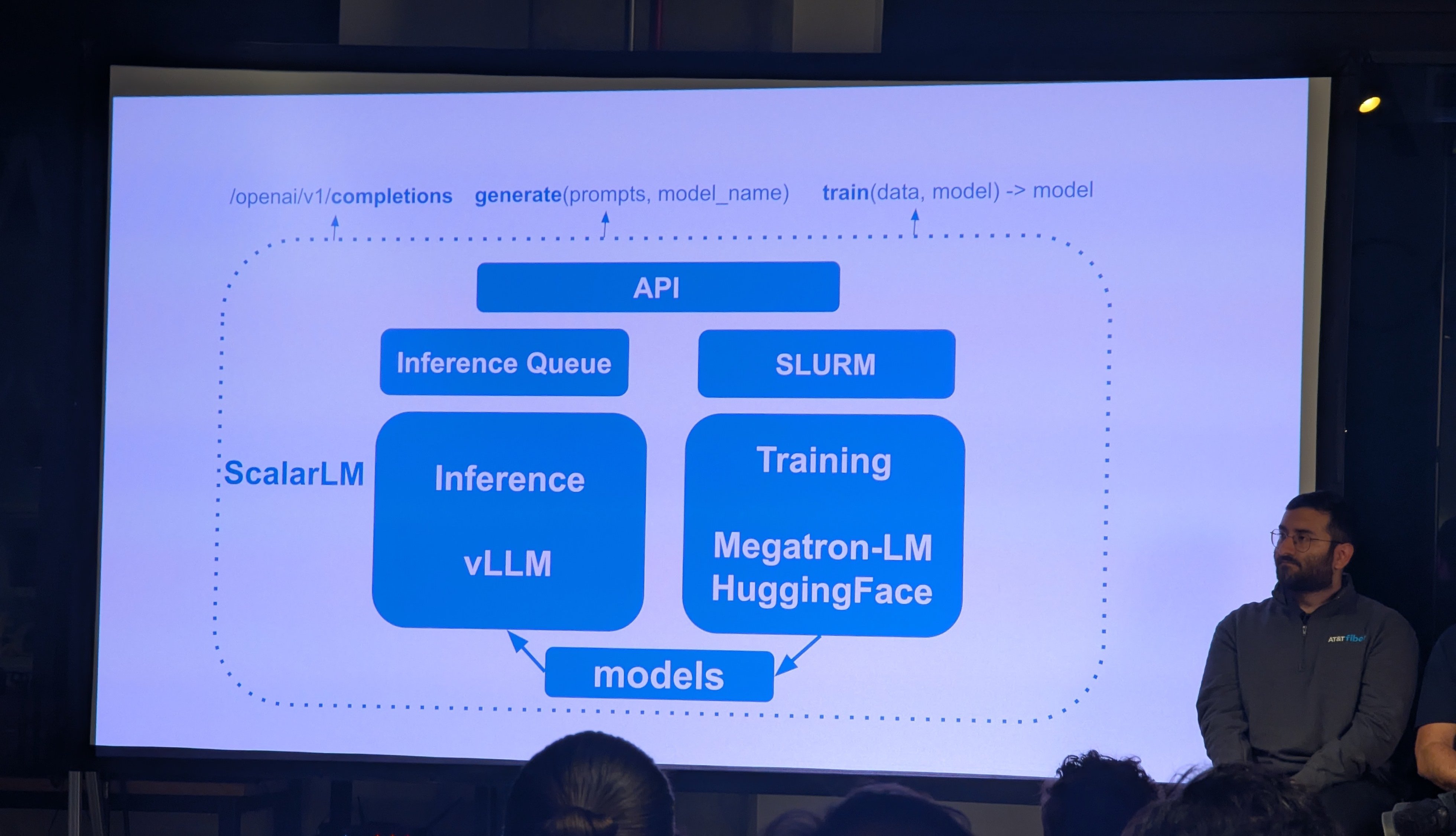

ScalarLM can run on the TensorWave cloud, and it is a framework that glues together Megatron-Core (a PyTorch training building-block library developed by NVIDIA and ported to run on ROCm), vLLM as an inference engine, and can, in principle, be used for inference or fine-tuning of any model available on HuggingFace.

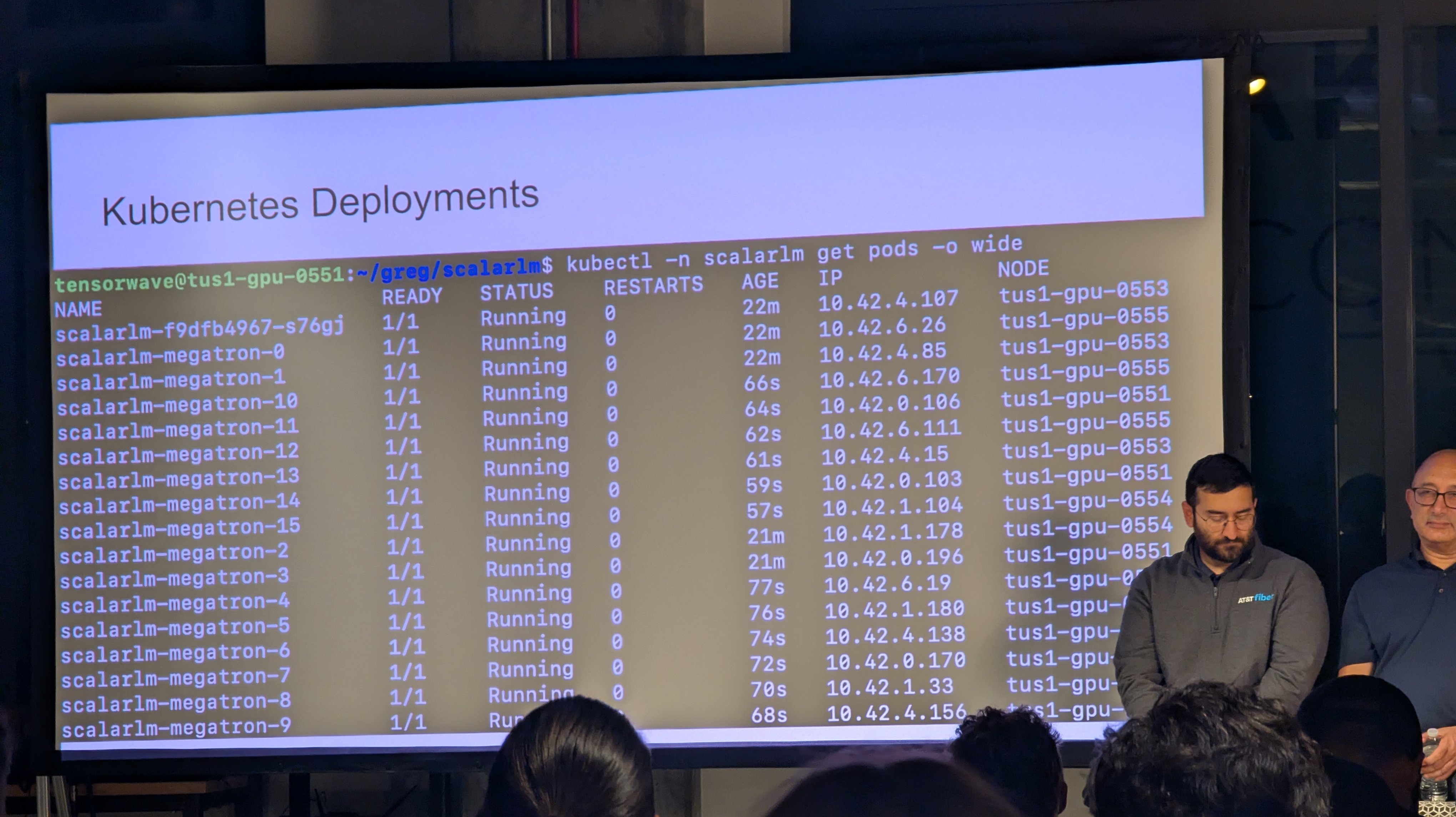

This was followed by a few slides discussing support for Kubernetes deployments on TensorWave and the high-level APIs provided by ScalarLM. Sure. Nice. But I could have just found this on the ScalarLM website2. And that was it for ScalarLM 😞. Switching gears now.

ScalarLM is very light on documentation; expected for such a new and understaffed project.

Time for Enterprise AI

Enterprises are very serious operations. AI is absolutely required to make critical business decisions. If you aren’t using the model to accelerate the decision making process, what are you even doing?

Mr. Model, what should I charge for these widgets to maximize profits?

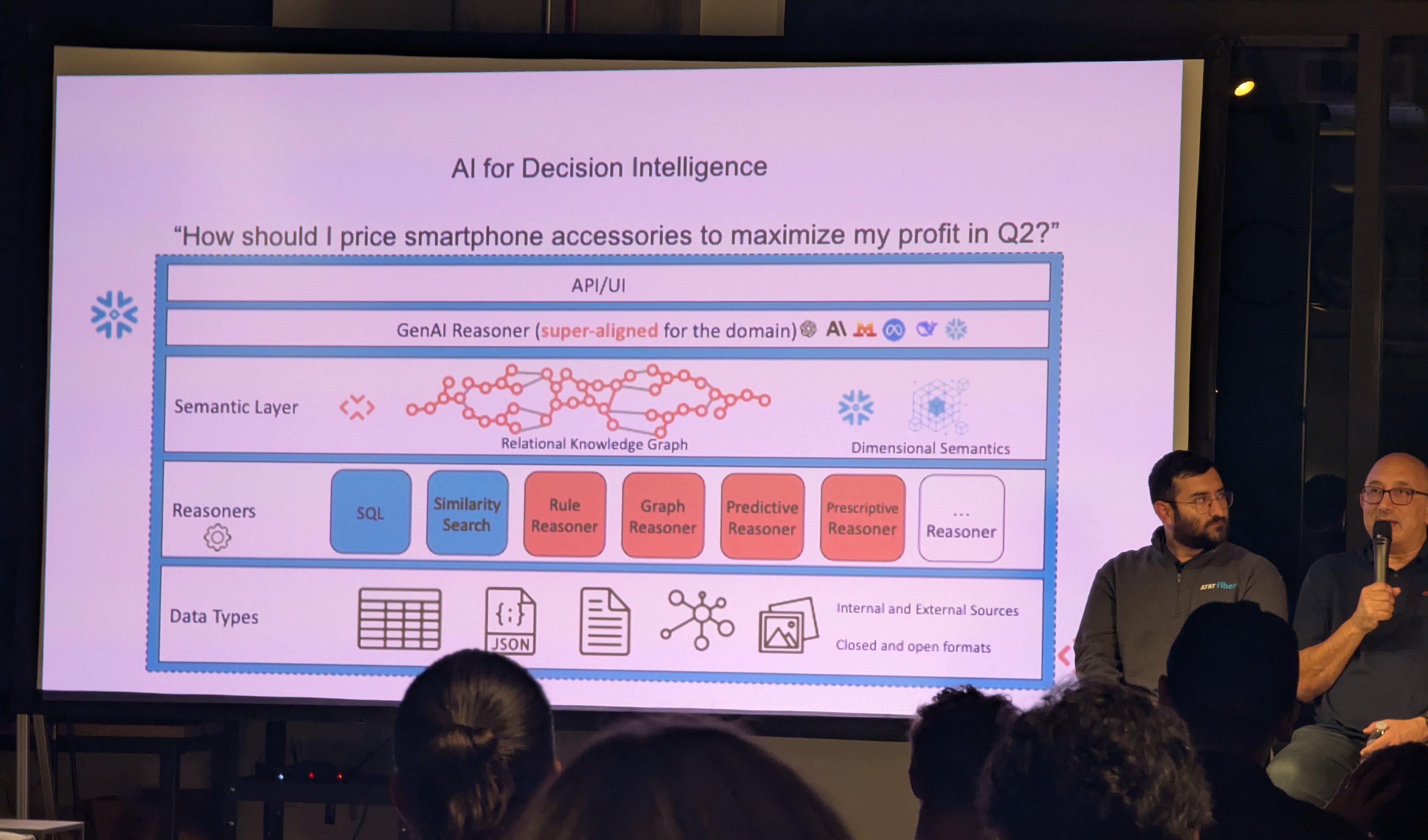

This part was presented by RelationalAI, a company that builds “decision agents” that are “aligned to your business”.

Rel, the decision agent, is here to help you make business decisions.

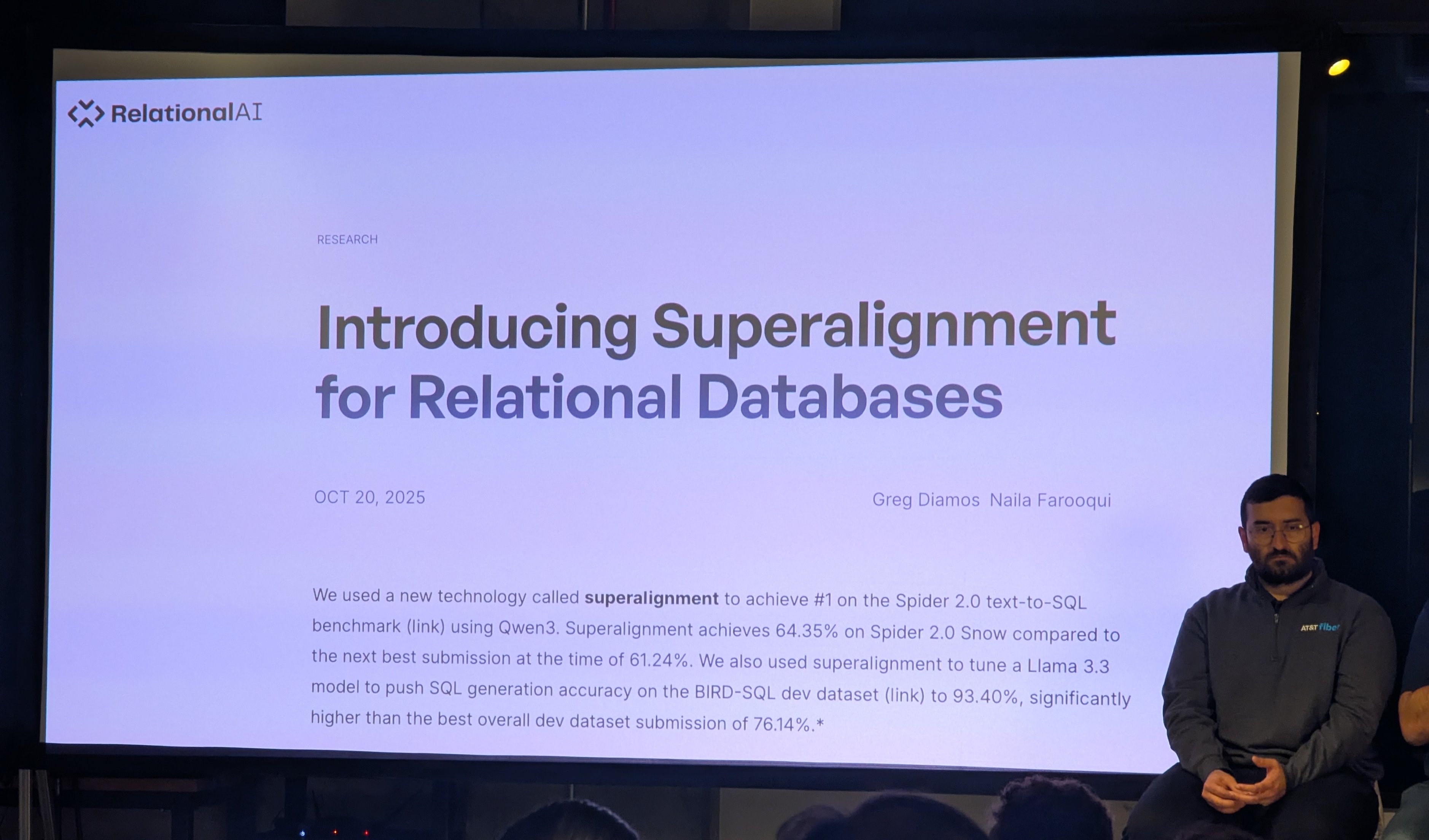

The RelationalAI guy stressed that “superalignment” of the foundation model was crucial to its performance in real-world tasks.

To be clear, the “superalignment” they’re talking about has nothing to do with the “superalignment” of the squealing AI safetyists. They are talking about fine-tuning, RAG, and context engineering using a business’ internal, domain-specific data.3 So what does superalignment enable?

I don’t mean to mock RelationalAI too much, it is a serious company

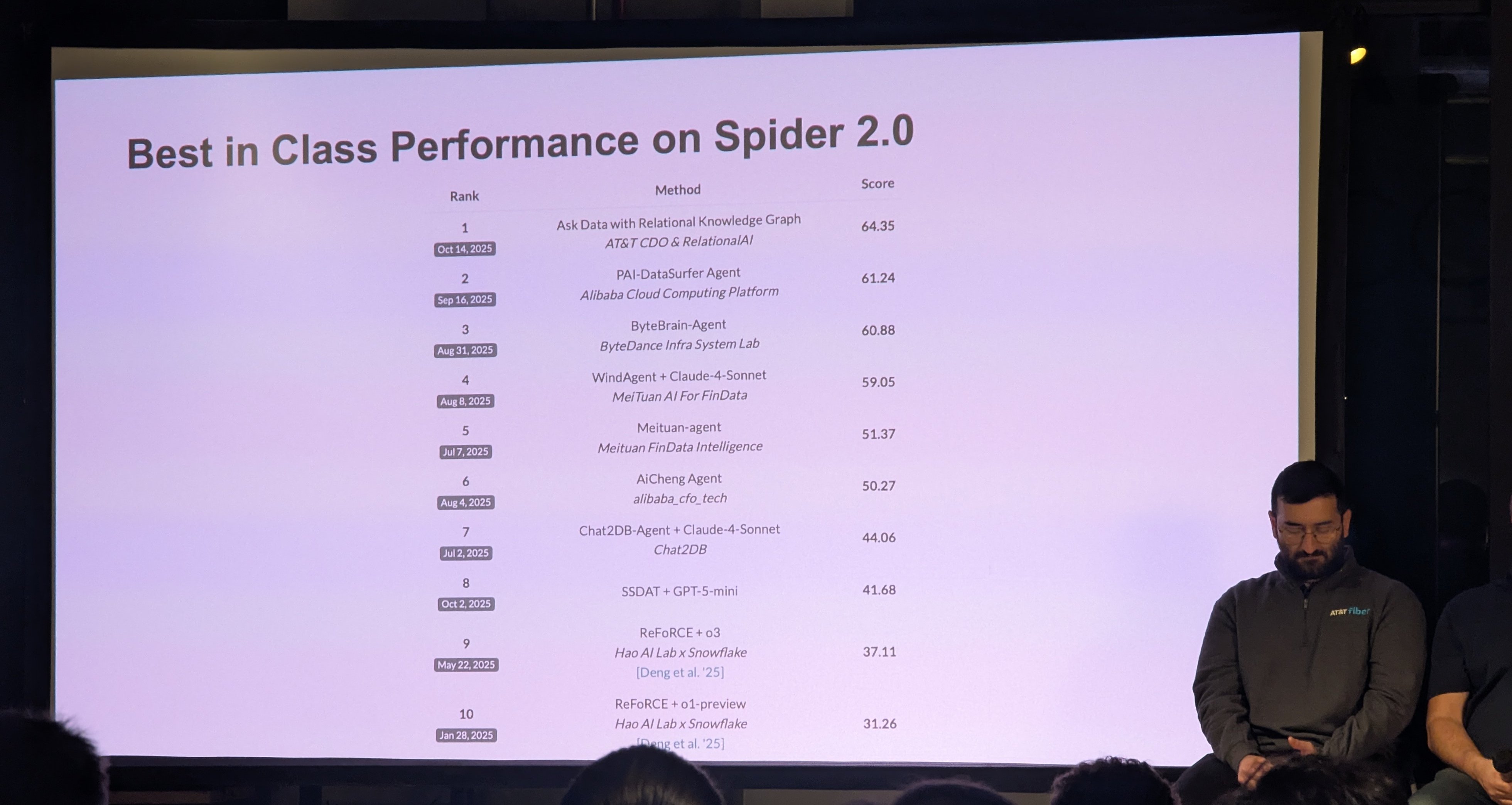

‘Superalignment’ for accurately writing SQL from English requests

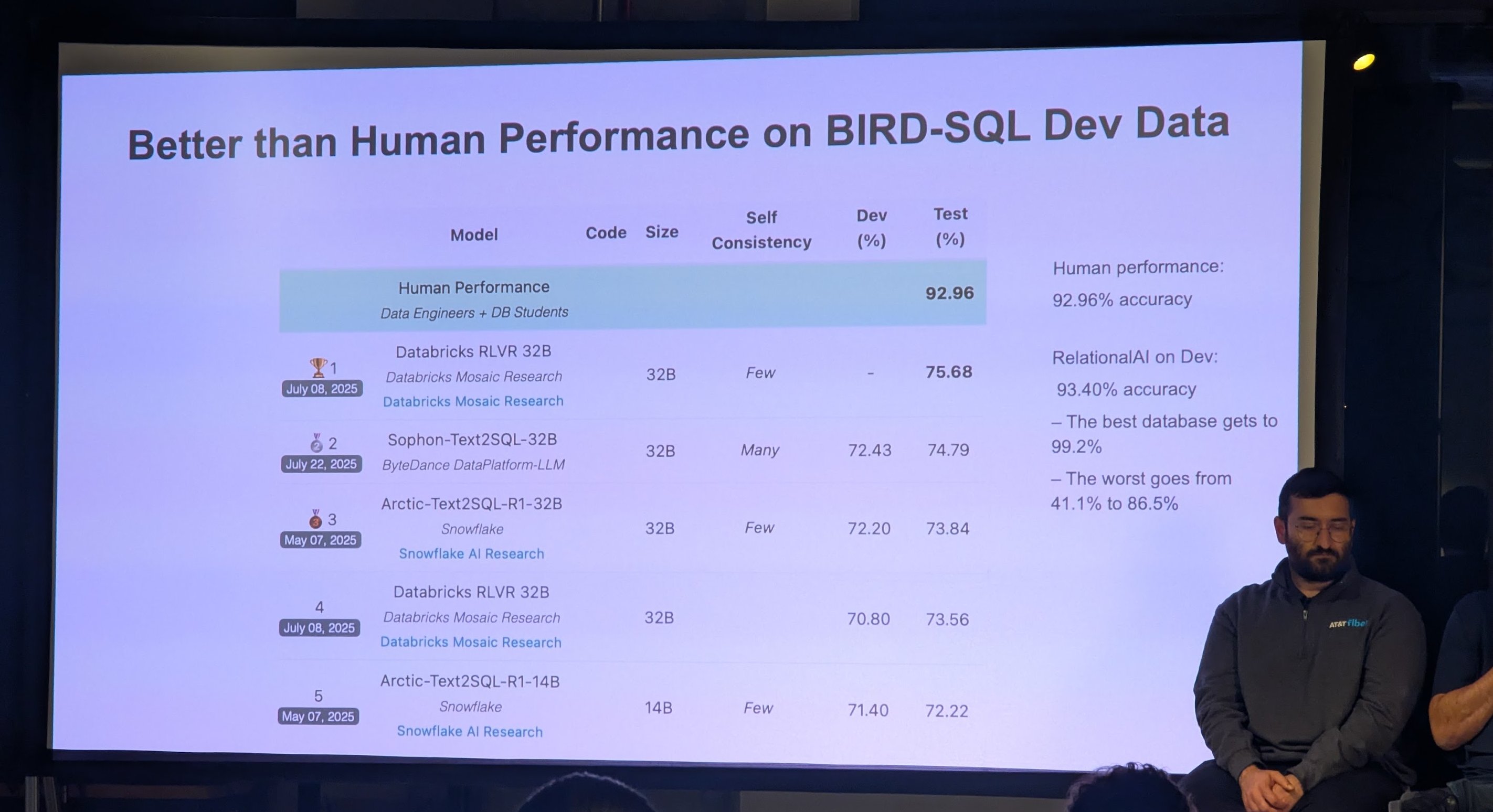

They presented improvements on a few text-to-SQL benchmarks: Spider 2.0 and BIRD-SQL Mini-Dev. With RelationalAI, we’re one step closer to being able to replace data scientists, thanks to the special sauce of “superalignment”. You may have noticed that this has nothing to do with AMD GPUs, TensorWave, or ScalarLM.

AT&T ‘Telco’ Fine-Tuning

And now, for the highlight of the panel. Behold, the “enterprise” use case for ScalarLM, presented by a data scientist from AT&T.

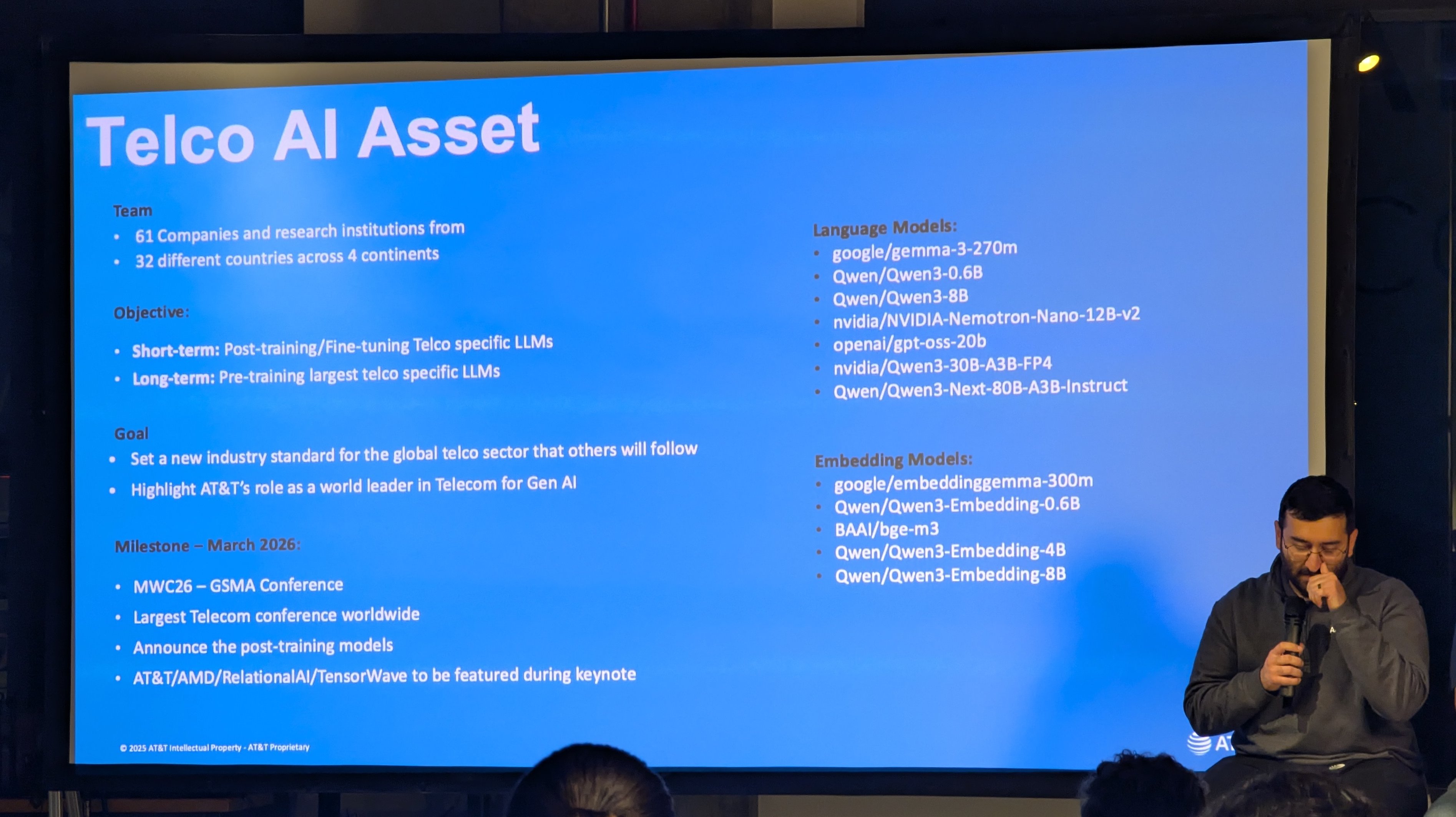

The enterprise needs AI. And the AI needs to be fine-tuned with the domain-specific knowledge required to answer questions. In the case of AT&T, that means they need a fine-tuned foundation model with knowledge of ‘telco’ facts: a telco-specific LLM.

Just ask the AT&T model

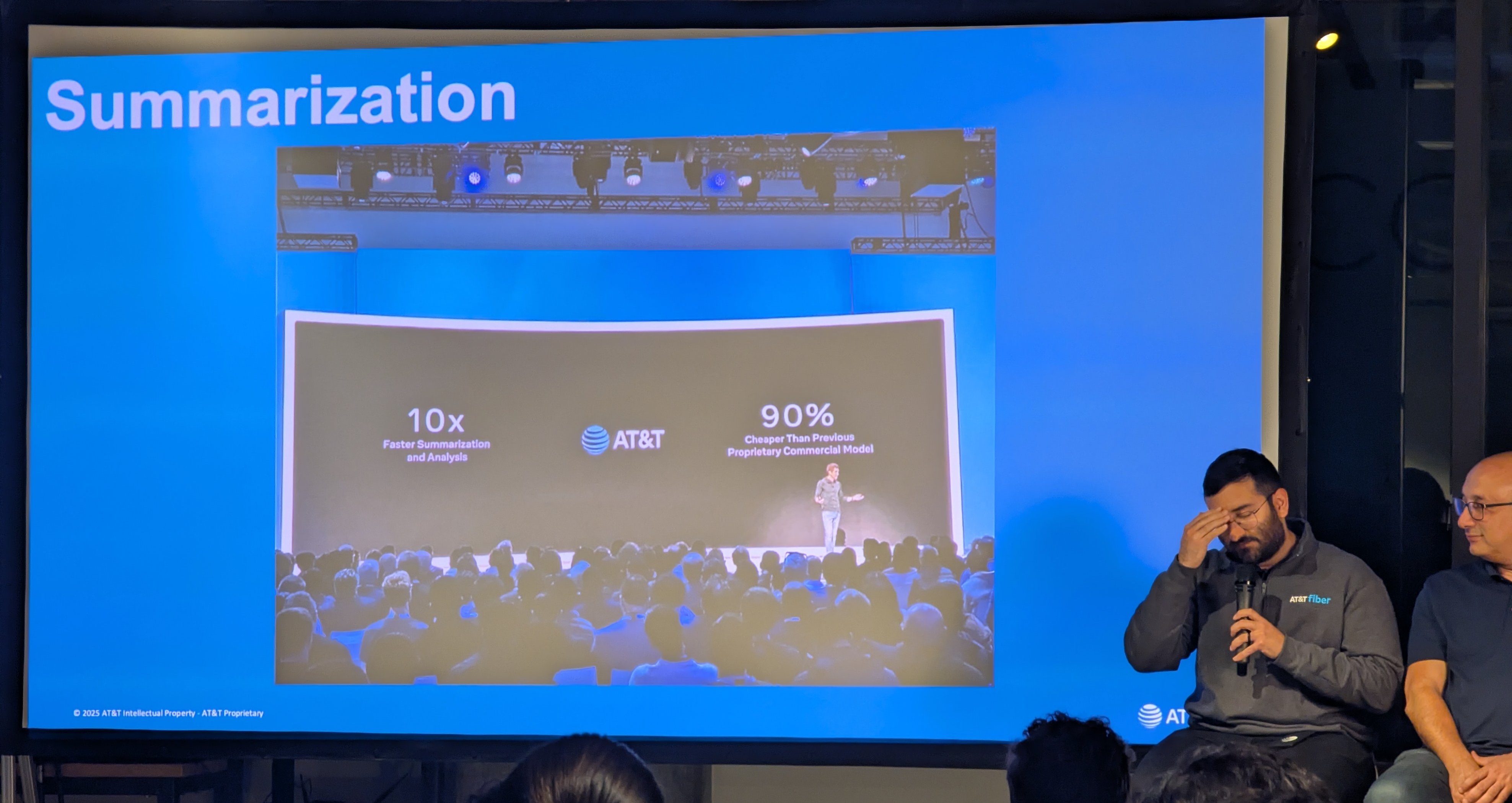

So they fine-tuned Gemma 4B using ScalarLM on a TensorWave cluster to do a good job at recalling and reasoning about “telco-specific” facts.

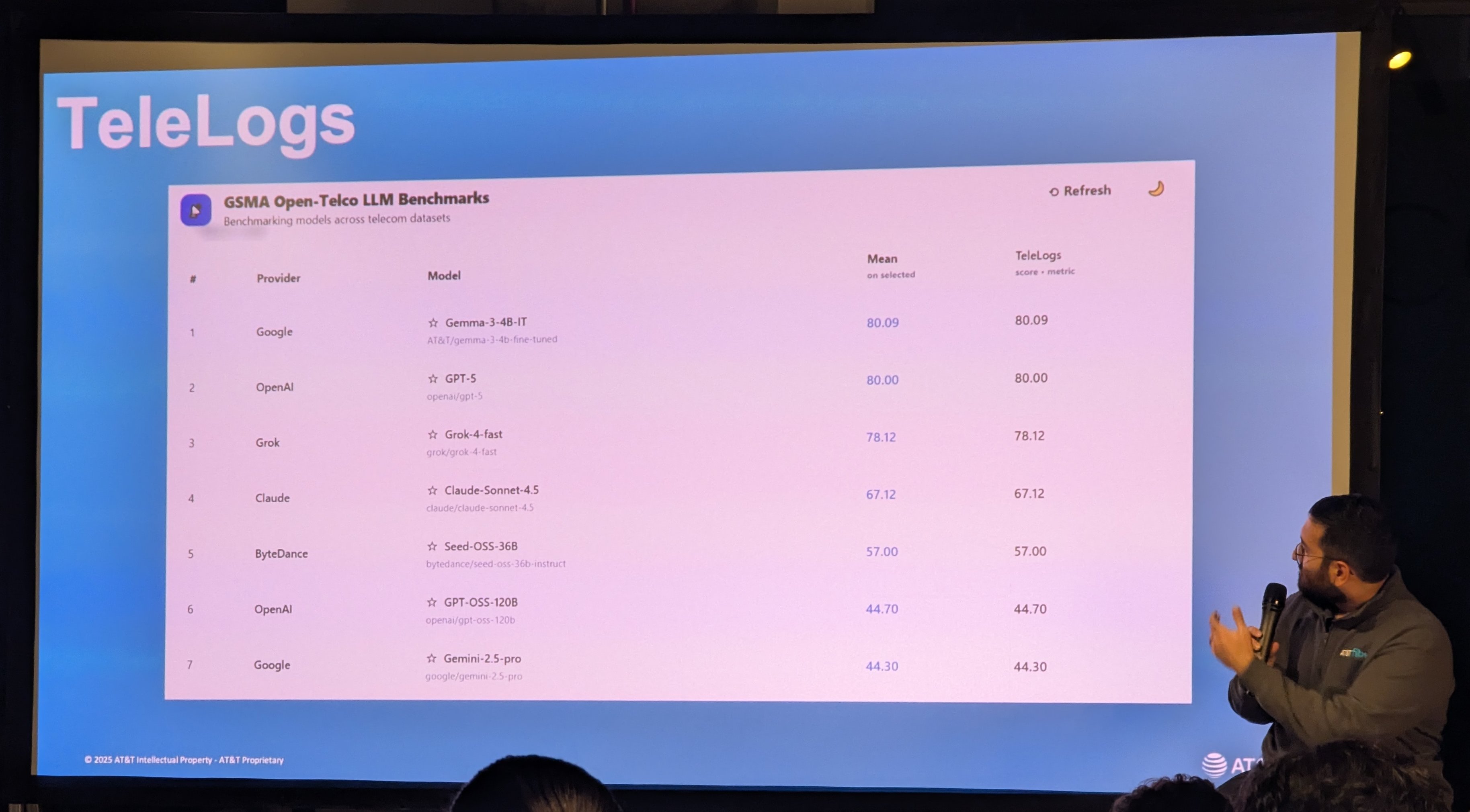

This fine-tuned tiny model outperforms GPT-5 by 0.09% on one specific category (TeleLogs) of the GSMA Open-Telco LLM Benchmark (see the full leaderboard here). Very good. Good job guys. Now AT&T can deploy a tiny model themselves to service telco-specific token generation and save some money.

Money saved! Tokens away!

And with that, the panel was over. Now that the panel discussion is out the way, I’ll pull together some comments from various attendees and my own thoughts.

TensorWave and AMD Today

Here is what TensorWave had to say about this event:

Last week at Open Source Week in SF was a blast.

— TensorWave (@tensorwave) October 28, 2025

Packed room. Smart questions. Bold ideas.

Thanks to @ATT, ScalarLM, and @RelationalAI for an awesome conversation on where open-source AI is headed and how @AMD Instinct GPUs unlock what’s next. 🚀 pic.twitter.com/0G4F7PsRux

But now my take: first on TensorWave. Why do these guys continue to host these kind of events that just degrade confidence in AMD and make their GPUs look like a joke? The events are run so professionally with lots of photographers, event planners, and so forth. But the content is so lackluster, which makes AMD look way worse than what they deserve.4

AMD has come a really long way in driver stability and PyTorch support

The TensorWave people are actually very competent! These kinds of events don’t showcase that competence. TensorWave is a serious company with good datacenter engineers — they raised a $100M Series A and they have the largest MI325X/MI350X cluster in production. Just recently, SemiAnalysis unveiled their ClusterMAX 2.0 ratings which placed TensorWave as a Silver-tier GPU cloud5, on par with Google Cloud, AWS, and Lambda.

Just 7 months ago, TensorWave was a Bronze-tier GPU cloud on ClusterMax 1.0 — rapid progress!

Regarding this event, TensorWave signed up around 250 people, but there were perhaps 50 people who attended, including the TensorWave employees. I understand it was a free event held during the busy AI Week with many other overlapping events, but still. The empty space, with stacks of boxes of uneaten pizza and plenty of wine and White Claw to spare, made the event feel even more lackluster.

From speaking with attendees, it seems that TensorWave is actually not bad at all from a technical perspective. They’ve improved their rack and cluster-level networking, and things are now quite reliable and stable for long training runs. The telemetry they offer is decent and their provisioning speed is also acceptable. It seems they are the best when it comes to AMD neoclouds, and their systems can be used just like any other tier-1 GPU cloud. I haven’t tried the TensorWave cloud myself, but my impression is that it has improved substantially over the past 6 months.

However, on AMD’s side, things are still not that great (compared to NVIDIA). I heard that the driver stability and the quality of their software stack is, in general, middling. They are slow to respond to bug reports and there are still problems in their cross-GPU communication / collectives library — rccl.

Jensen Always Wins

Going back to what was presented in the panel, what does any of it really have to do with TensorWave or AMD GPUs? Here is my take on why someone would choose to use AMD GPUs today:

- Pricing

On Lambda, you can get a H100 for $2.49/GPU/hr or a GH200 for $1.49/GPU/hr and a reserved H100 cluster goes for $1.85-$2.29 per GPU-hr. A B200 HGX reserved cluster goes for $3.79/GPU/hr.

On TensorWave, you can get a reserved MI325X/MI350X cluster for $1.95/$2.85 per GPU-hr. If you’re chasing value and short runs, you can get an on-demand MI300X on Hot Aisle for $1.99/GPU/hr.

Pricing is basically a wash — perhaps a slight advantage to AMD. However, AMD does have a significant advantage when it comes to HBM capacity per GPU.

- Negotiating leverage

This is tightly coupled with the pricing argument. The argument goes, if your application can only run on NVIDIA GPUs, then you are forced to pay whatever tribute Jensen demands. Therefore, you should diversify your hardware to build negotiating leverage against NVIDIA.

The importance of having negotiating leverage mainly applies to hyperscalars or frontier AI labs who continuously purchase massive quantities of GPUs. The token consumers and fine-tuners (like AT&T) will almost always choose to rent GPUs, or buy such small quantities that their leverage is minimal.

- Availability

While NVIDIA GPUs are in very high demand, NVIDIA has far more cloud deployments than AMD. I can’t comment on how easy it is to reserve a large NVIDIA Blackwell cluster, but it would seem that the immense volume and large number of NVIDIA hyperscaler clouds and neoclouds makes it easier in practice to rent an NVIDIA cluster vs an AMD one.

Considering points ⓵, ⓶, and ⓷, unless you were penny-pinching, why would you bother to use AMD GPUs? Using AMD is often not cheaper once you factor in the opportunity cost of the time spent porting software and getting optimal performance.

In 2024, Jensen reminded everyone of this important fact:

When you see computers these days, it is a datacenter, and you have to operate it. So the people who buy and sell chips think about the price of chips, but people who operate datacenters think about the cost of operations.

Our time to deployment, our performance, our utilization, our flexibility across all these different applications, in total, allows our operations cost (TCO), to be so good, that even when our competitor’s chips are free, it’s not cheap enough.

AMD couldn’t give their chips away for free; they had to give away their equity too. In contrast, NVIDIA can take equity from the AI labs while selling them their chips. This lopsided situation isn’t an accident.

An AMD Cloud Provider Perspective

The competent operator of the AMD-only cloud Hot Aisle, made this interesting remark about TensorWave (TW):

I track @AMD NeoCloud compute pricing closely.

— Hot Aisle (@HotAisle) November 16, 2025

What stands out:

TW is cheaper than Vultr on MI325x, yet remains 10% more expensive on MI355x. Both clearly have capacity available, which means they’re mostly landing short-term PoCs, small jobs, or deals below list price.

TW… pic.twitter.com/SFNcMNYVMC

Here’s the full quote:

I track @AMD NeoCloud compute pricing closely.

What stands out:

TW is cheaper than Vultr on MI325x, yet remains 10% more expensive on MI355x. Both clearly have capacity available, which means they’re mostly landing short-term PoCs, small jobs, or deals below list price.

TW being sold out of MI300x but not sold out of MI325x (July delivery) or MI355x (August delivery) signals weaker than expected demand for both. They have inventory, and they haven’t locked it down with long-term contracts. Why not?

Where’s the profit?

TW financed those GPUs through DDTL (~$100M+), likely at 8.5–14% interest, along with investor funds. That’s a massive hit over the last five months, one they’re not getting back. Add ~80 employees to the burn, 4 office moves, and sure, revenue comes in… but sustainable long term profit? I know exactly what this stuff costs, not even close.

The business model of TensorWave is fishy, but not that different than the other neoclouds.

The CUDA Moat Today

To understand NVIDIA’s continued dominance, I’ll go over the big GPU markets and how they are served by NVIDIA’s programming model and software.

GPU Markets

I think there are 5 significant markets for GPUs today:

- Gaming

This was the original GPU market, but it has declined in importance in the past 5 years. Since this market is shrinking as a percentage of total revenue, being competitive in gaming isn’t good enough for AMD. AMD serves the gaming market just fine with slightly cheaper and more available consumer GPUs vs NVIDIA. 3D rendering APIs (DirectX, OpenGL, Vulkan) generally work well enough regardless of GPU vendor.

- HPC / workstation applications

GPUs are used in all kinds of HPC applications such as, CAD (AutoCAD, SolidWorks), CAE (FEA / CFD / MBD tools), weather simulation, 3D rendering (Blender, Maya), astrophysics, computational chemistry, data processing, medical imaging, and so forth. These applications are often bespoke and domain-specific, and are also a small fraction of total GPU revenue.

However, NVIDIA has a strong advantage here. There are tons of custom CUDA kernels in all these pieces of software and the software developers have little incentive to HIP-ify them (more on this later).

- ML Training

This is the largest GPU market by revenue so far, but will be (or perhaps already has been) eclipsed by ML inference. ML engineers want to write PyTorch and have the compiler handle everything else. In practice, after some experimentation, the top labs will have engineers hand-write CUDA kernels (or tune a higher-level compiler/DSL such as Triton/Gluon or JAX/Pallas) for production training runs — they will try their best to max out the utilization of each GPU and network resources.

NVIDIA (and TPUs within Google) dominates training because developers will use and optimize for the most available platform. This is not only a function of what hardware is easy to get, but also the availability of turn-key software. When the Chinese AI labs explore new model architectures, they write kernels in CUDA, and never look back.6

This may be changing due to Chinese government controls. Chinese kernel devs will be bludgeoned just like the Googlers.

- ML Inference

This market resembles the training one, but there are many more custom chip startups (e.g Tenstorrent, Groq, Cerebras, SambaNova, d-Matrix, MatX) and hyperscalers (e.g. Meta, Microsoft, AWS, Google) getting into the inference game, while most labs still rely on GPUs for training.

Since inference is expensive to run, it is worth exploring cheaper NVIDIA alternatives to boost token API margins (most notably AMD, but also TPUs and Inferentia). AMD has the best showing, but their rack-level and cluster-level networking is still behind what NVIDIA offers. The most important thing is turn-key inference serving with vLLM, SGLang, TensorRT-LLM, or even Modular MAX. NVIDIA is well supported in every inference serving engine and for every AI model in existence, while AMD still has a way to go.7

It may appear that vLLM has support for ROCm, but practically, the out-of-the-box experience / performance isn’t comparable to NVIDIA (especially for multi-GPU setups)

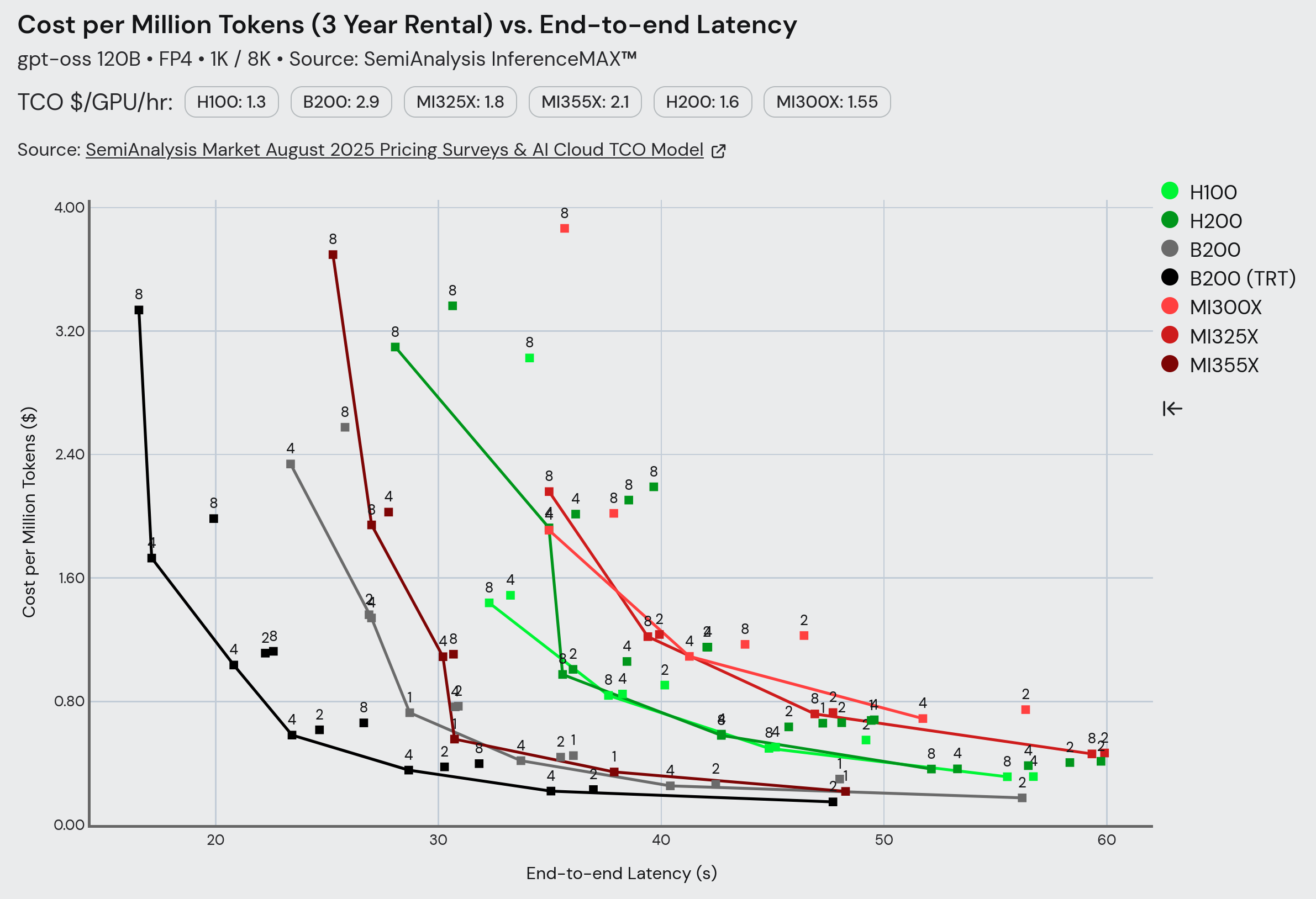

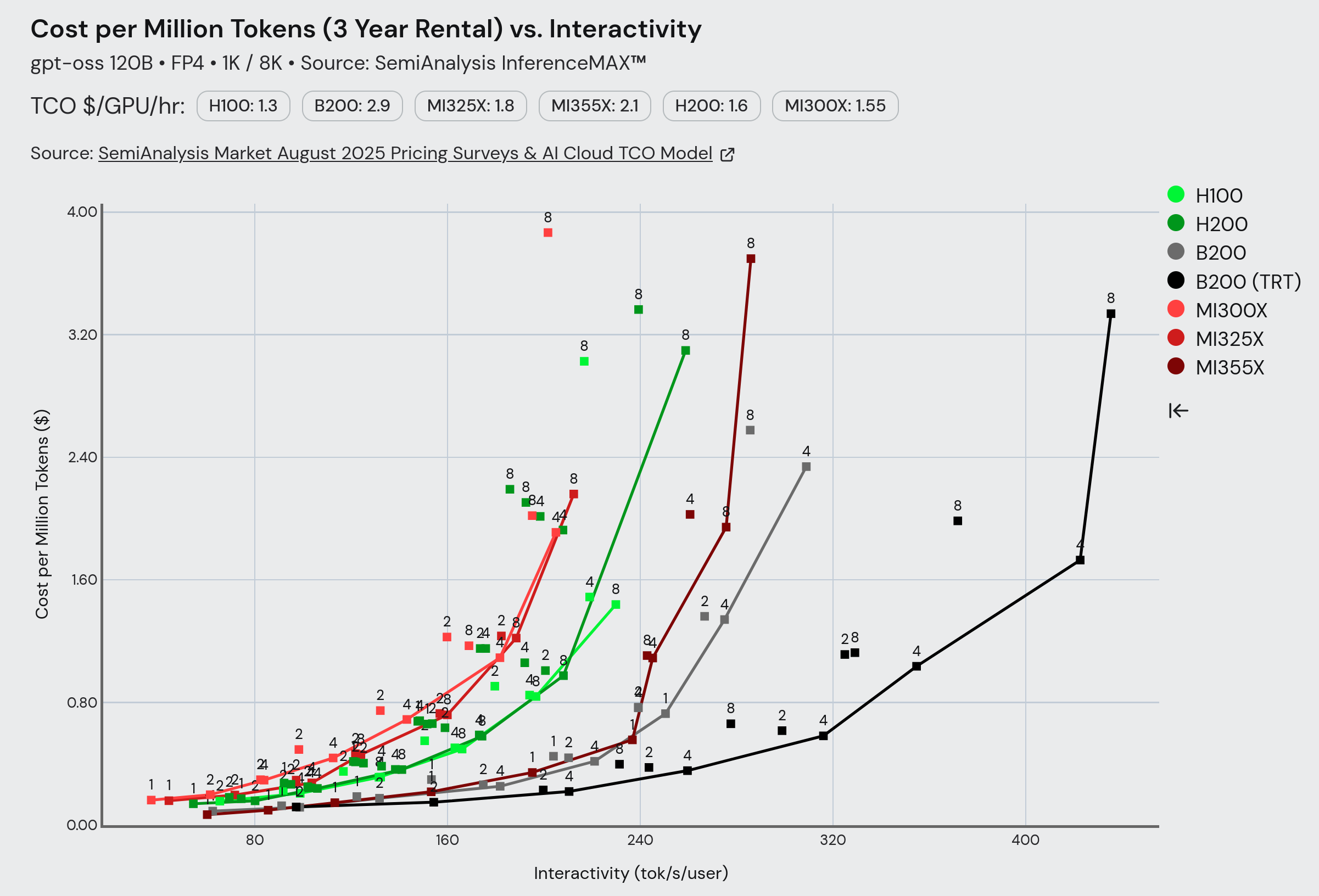

Recently, SemiAnalysis put out their InferenceMAX benchmark. If we look at decode-bound scenarios (i.e. ‘agentic’ workflows), AMD is reasonably close to, but still behind NVIDIA, on raw $/token for medium-sized models.

InferenceMAX results for gpt-oss-120B 1K/8K on November 11, 2025

- Edge

Think about applications like VR headsets, smart cameras, and autonomous vehicles. In the low-power domain (sub-10W), there is plenty of competition, but low margins. However, in the high-performance tier (required for robotics and AVs), the NVIDIA Jetson series of products completely dominates with basically zero competition.

Why is CUDA Great?

Nicholas Wilt, who was on the original CUDA dev team, made a few tweets that summarize why NVIDIA was able to capitalize on all five of these GPU markets. In short:

- NVIDIA emphasized portability from the very beginning, supporting both Windows and Linux, and implemented their APIs in pure C

- CUDA supports flexible software integration, providing both a driver and runtime API

- NVIDIA supported CUDA across all its product categories (mobile, desktop, and datacenter). This is something AMD still doesn’t do today, but has promised for the future

- CUDA C++ device kernels generate PTX, a stable SIMT ISA. PTX enables the driver’s JIT compiler to abstract away the churn of the machine ISA (SASS) across GPU generations

I wouldn’t be able to outdo Wilt when it comes to extolling the virtues of CUDA, so I’ll just reference two of his articles that you should read: “Ten Years Later: Why CUDA Succeeded”, “Ten Years Later: CUDA Succeeded Despite…”.

NVIDIA does a great job separating parts of their compilation stack (CUDA C++, PTX, SASS, low level machine code) so they can always make changes in the lowest layer and just make all software compatible via the low-level JIT compiler. AMD doesn’t seem to know how do to this so kernels just suddenly stop working on future GPU generations - at least NVIDIA kernels always work, albeit with per-architecture performance tuning being necessary.

More modern trend of NVIDIA trying to expand CUDA from CUDA C++ into PyCUDA (new frontend language) and CuTile (new abstraction) and new Python CUTLASS (new abstraction and low-level code metaprogramming generator). NVIDIA isn’t stopping. CUDA Python, cuTile, Warp, CUTLASS Python, numba-cuda

- nvidia cuda kernel stack gtc (attach image)

Lessons from Dojo

- Dojo stories. No precise exceptions. No step-by-step debugger. No compiler. No pre-silicon emulator. And all these and more led to the failure of Dojo.

- The importance of building the entire software stack BEFORE tapeout is so essential. AMD can’t do this. Nearly all SW dev only happens after the silicon is back and brought up. The internal uarch is a total mess.

- NVIDIA does this all the time. They have a robust chip emulator. Firmware and drivers are nailed down before the silicon is back and it’s running full workloads on the power up day.

Dojo exposed the hw redundancy directly in the isa, like the cores were fused off per device and the compiler has to reason about that lol, another reason for failure

The importance of cleanly separating architecture and microarchitectute, this makes all the difference to build a robust compiler, ergonomics are so important, Nvidia did this right

But do LLM generated kernels make this obsolyet thinking? If karpathy is right that llms aren’t thinking machines but rather human spirits, then I don’t think the spirits would be happy with a broken compiler and exposed uarch details everywhere lol.

If language models can reason from documentation and code analysis and perhaps the PTX spec alone, then why would examples be a limiting factor (all the libraries you mentioned have their code open source)? What to you appears to be the fundamental limiter for how models can write CUDA code? What are the failure modes you see?

There is something here that is a bit subtle. CUDA kernels are amenable to model autonomous iteration because they manage to separate enough microarchitectural details from the architectural ISA. If this isn’t the case, I suspect LLMs would perform much worse - consider the Groq or Dojo ISA.

NVIDIA’s Open Source Strategy

- https://x.com/SemiAnalysis_/status/1980840184905158712

Meta has open sourced their CTran library that natively works with AMD & NVIDIA GPUs 🚀. Previously, if u want multiple NVIDIA GPUs to work together on an workload, you must used the NVIDIA NCCL library. Although NCCL’s source code is public, it does not have an open governance model, does not have open CI, employs an “code dump” update model, is not GitHub first, and rarely accepts external contributions. Previously, If you want multiple GPUs to work together on an workload, you must used the AMD fork called RCCL library, which is a delayed fork of NVIDIA’s NCCL. With CTran, it is 1 unified library and allows for adding new like Bruck’s in an way such that the code can be shared between different AI GPU types.

Furthermore, Meta has open sourced NCCLX (NCCL extended) which is their production-tested collective library that powered all Llama training and uses the unified CTran library. Meta is the creator & main maintainer of PyTorch and is well trusted in the open source community.

NVIDIA continues to be the leader in collective libraries but Jensen must not taken it for granted given the heavily increased competition in the open source collective communication space. Just like how TRTLLM moved to an GitHub first development when facing heavy competition from SGLang/vLLM, Jensen should seriously consider moving NCCL to GitHub first open development model due to the competition in the collective front too. To draw parallel comparisons to the inference engine world, Collective Communication Libraries are moving from the 2021 “FasterTransformer” era to the 2025 “SGLang/vLLM/TRTLLM” era.

The main competitors in the collective library space include China’s DeepEP library, AMD’s new MORI, AMD’s upcoming MORI-CCL, Meta’s CTran & NCCLX, NVIDIA’s NCCL (which has released their new NCCL Device API, NCCL’s new GPU-Initiated Networking, etc). Competition breeds innovation! 🚀

Future of Kernel Languages

-

https://x.com/clattner_llvm/status/1982196673771139466

-

1st gen: CUDA C++

-

2nd gen: Torch, TensorFlow -> Python eDSLs, eager execution of GPU kernels written in CUDA C++ (CuBLAS, CuDNN)

-

3rd gen: TVM, Triton + Gluon, JAX + Pallas -> compilers + binding/scheduling DSLs to recover performance with manual interventions

-

4th gen: Mojo, CUDA Python? back to writing kernels like CUDA C++

-

https://www.modular.com/blog/democratizing-ai-compute-part-6-what-about-ai-compilers

-

https://x.com/tinygrad/status/1982634315520651498

BREAKING: The CUDA moat has just expanded again! PyTorch Compile/Inductor can now target NVIDIA Python CuTeDSL in addition to Triton. This enables 2x faster FlexAttention compared to Triton implementations. We explain below 👇

— SemiAnalysis (@SemiAnalysis_) November 19, 2025

As we explained in our April 2025 AMD 2.0 piece,… pic.twitter.com/sJMLTzylo3

BREAKING: The CUDA moat has just expanded again! PyTorch Compile/Inductor can now target NVIDIA Python CuTeDSL in addition to Triton. This enables 2x faster FlexAttention compared to Triton implementations. We explain below 👇

As we explained in our April 2025 AMD 2.0 piece, Python DSLs for kernel authoring represent the future—not C++ templates. NVIDIA has been massively supporting their closed-source Python CuTeDSL, cuTile, and TileIR ecosystem. By having Python CuTeDSL/cuTile/TileIR, NVIDIA regains closed-source compiler optimization passes, whereas in Triton, the middle-level IR optimization passes are open source.

Furthermore, Triton currently lacks strong Blackwell performance as it doesn’t yet support Cluster Launch Control and 2SM MMA with TMA multicast. Triton IR will support be able to target TileIR too. While Gluon attempts to address this, it remains a work in progress.

Google has also integrated an experimental backend for TorchInductor to target Pallas for codegen. It’s unclear when AMD will release/integrate Wave DSL or ComposableKernel Python DSL into Torch Inductor as a codegen target.

Spectral Compute

-

The Spectral Compute guys (https://scale-lang.com/) are taking another approach where they target the CUDA frontend directly! But this is mired in difficulty as they need to replicate all the functionality and subtleties of nvcc going down to PTX. And they need to handle the warp size being 64 on AMD but 32 on NVIDIA, which needs hacking at the source level.

-

Dedicated address registers (with addressing modes encoded in the opcode and direct memory manipulation ISA) + vs unified load/store architecture for SIMT machines…

- Hard to say. If you have scalar runahead and a decoupled post-commit vector machine like SiFive does, then this wouldn’t buy you much and would make the register space fragmented, making compilation harder

- But for a SIMT machine where you have in-order vector instruction dispatch and limited opportunity to amortize the cost of multiple RISC instructions, perhaps this would make sense. Allowing physical separation and banking of the RF would be advantageous too from a PD and timing perspective, but it is hard to say what it would buy you for the tradeoff of more spills and compiler complexity.

-

https://x.com/SpectralCom/status/1987909075015733590

You can’t start a hardware rebellion without funding.

So we went and got $6M.

Our CEO Michael Søndergaard just broke down our entire plan to end vendor lock-in with @RobertScammell at @BusinessInsider.

We’re even open-sourcing our battle plans (aka the pitch deck). Read it.

-

https://www.businessinsider.com/spectral-compute-funding-pitch-deck-nvidia-cuda-2025-11

-

https://x.com/SpectralCom/status/1993289178130661838

A great question we’ve been asked a lot at #SC25 is “Why does #NVIDIA not sue you to oblivion?”. Well, this is due to many reasons.

We don’t reverse engineer nvcc or violate EULAs. We implement our compiler on the latest LLVM backend and Clang frontend. We strictly rely on public API documentation, we don’t use any proprietary header files or source code as reference.

Google v. Oracle protects computer programs and software libraries “developed by recreating the functionality of APIs from commercial or competing products to aid developers in interoperability between different systems or platforms.” - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_LLC_v._Oracle_America,_Inc .

We implement SCALE via black-box testing. Our unit tests validate that our operations match CUDA outputs within floating-point tolerances, so that we get mathematical equivalence without inspecting implementation logic.

We validate our assumptions by testing SCALE against third-party open source CUDA projects. You can check them here - though we’re in the process of updating the repo, as compatibility has improved a lot lately.

And then there’s a commercial point to be made. SCALE allows developers to stay in CUDA while retaining the option to deploy elsewhere. This safety net encourages new projects to start - and stay - in CUDA.

And then there’s a commercial point to be made. SCALE allows devs to stay in CUDA while retaining the option to deploy elsewhere. Rather than being a competitive threat, SCALE is actually a complementary ecosystem enabler.

We built this the hard way so you don’t have to worry about it.

Judge for yourself at http://scale-lang.com.

Replies are open for questions, technical deep-dives, or armchair legal analysis. 👇

- https://x.com/tinygrad/status/1993365249098170626

This isn’t why. Trying to “compile” CUDA for AMD is nonsense; NVIDIA loves when people try. CUDA will never be fast on AMD (how do you compile if the shared memory / tensor cores are a different size?). It’s the wrong layer to do this at.

HIP is literally clang-dialect CUDA: it isn’t a different programmnig language, so there’s no difference there. NVIDIA currently sell GPUs with at least 5 different shared memory sizes, and at least 3 different tensor core sizes. CUDA already has features for modelling these types of difference: we’re doing the compiler R&D to take it further to work well on AMD.

NVIDIA have done a superb job of convincing the world that CUDA is somehow magically optimised for their hardware. Is C “optimised for Intel CPUs”? Is Rust “optimised for AMD CPUs”? Of course not: this is a compiler problem, not a programming language problem.

Btw, if you’d like to read about some examples of us hiding hardware differences optimally across platforms, this is our latest whitepaper: (“Optimizing CUDA Shuffles with SCALE”)

ZLUDA

-

ZLUDA has a revival! After it was shot down by AMD management (don’t want to be stuck with the CUDA APIs and let NVIDIA always make the first move) and legal (what if it is illegal to work on PTX directly?), it seems those very smart guys moved out of AMD and kept working thanks to external funding coming online. (https://github.com/vosen/ZLUDA)

- This might be the future of anything working on AMD

- AMD actually tried to go back on their contract with the ZLUDA people (https://zluda.readthedocs.io/latest/faq.html) and take down their open source repo when AMD said they wouldn’t move forward with it (even though that was permitted in their contract). Very insane lawyers who went crazy and sabotaged AMD’s future.

-

AMD has tried to force tier-1 SW companies to HIP-ify their kernels (think Autodesk, Adobe, …). It has mostly been a failure with billions lost in time alone. A CUDA emulation layer is crucial and the obvious way to get decent software support quickly. Trying to make people rewrite kernels just isn’t going to work.

-

On the other hand, even though HIP and so forth for HPC / workstation software won’t work logistically, since RoCM has decent support in PyTorch / JAX (?), it should be possible to make porting most DNN workloads easy. Still isn’t the case due to custom CUDA kernels everywhere, but technically doable. Especially once they have a working Triton/Gluon backend that is as robust as the NVIDIA one.

-

Have to reimplement cuDNN and cuBLAS and other CUDA libraries that are linked in as blobs. Or really? Check the documentation for ZLUDA. Perhaps they can directly emulate the PTX that comes out of these libraries.

-

https://www.phoronix.com/forums/forum/hardware/graphics-cards/1582320-zluda-5-released-with-an-offline-compiler-for-cuda-on-non-nvidia-gpus

-

https://vosen.github.io/ZLUDA/blog/zluda-update-q4-2024/

-

https://vosen.github.io/ZLUDA/blog/zludas-third-life/

-

https://www.techradar.com/pro/a-lone-developer-just-open-sourced-a-tool-that-could-bring-an-end-to-nvidias-ai-hegemony-amd-financed-it-for-months-but-abruptly-ended-its-support-nobody-knows-why

-

https://eliovp.com/why-cuda-translation-wont-unlock-amds-real-potential/

- Why “CUDA” Translation Won’t Unlock AMD’s Real Potential

- A contrary take. Worth reading. From a company building dedicated ROCm kernels for LLMs - they are biased in their approach of course

- HN thread: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=45904178

DensityAI (OpenNova)

-

When Dojo was dismanteled at TEsla, some of the best people left to form OpenNova

-

It came out of stealth and was rebranded DensityAI

-

They claim to do automotive AI training chips, but I think this is misstep. They should just focus on high performance silicon in general

-

They are using all the knowhow from Dojo, which I think was the highest performance, most vertically integrated architecture in the AI chip space (massive power draw, very exotic and new wafer-scale packaging)

-

Take the ideas from Dojo and the people and build the next one, but sell it publicly. Don’t focus too much on inference-only workloads

-

OpenNova = wafer-scale integration of reticle sized logic dies that are co-packaged with HBM, and then mounted on a wafer-scale substrate. An ultra-high performance wafer-scale chip with crazy amounts of off-wafer bandwidth, just like Dojo.

-

But unlike Dojo, don’t neglect the software., which is what caused its downfall (as docuomented above)

- The key is ZLUDA! We suspect that ZLUDA development is being funded by DensityAI. Their chip will ingest PTX and work out of the box using CUDA emulation. That is my suspicion. And then it will have its own programming model which can be targeted using the usual chain of PyTorch -> some IR -> custom backend with backend-specific annotations / transforms.

-

Bloomberg: Former Tesla Executives Create Data Center Firm DensityAI

SF Hype Cycle Lunacy

We are living in an insane asylum

I think we’re near the top.